Exploring Rama, the platform for writing backends 100x more efficiently

- Why should you care about Rama?

- From the Rama introduction blog post

- From the docs

- From other sources

- Summary

- Read next

In 8/2023, RedPlanetLabs has unveiled Rama, their integrated platform for writing and operating robust, distributed, and scalable backends 100x more efficiently. With it comes a new paradigm - dataflow oriented programming. So what is it all about?

In this post I aim to give you a rough idea of what Rama is, what it offers, and why you absolutely should be interested in it.

Why should you care about Rama?

You should care about Rama, because it promises 100 times higher productivity when writing backends. But can it deliver? And what is a backend anyway?

In this context, a backend is a system responsible for storing and managing data - with all the business logic - to answer queries and handle commands from a user interface, such as a webapp.

Can Rama deliver? I can’t say yet. Their implementation of Mastodon is certainly impressive in terms of lines of code (LoC), performance, and scalability. And it compares very favorably with Twitter, though of course it is an apples to oranges comparison. (On the other hand, Nathan has worked at Twitter and has a good grasp of its scale and challenges.) What I can do is look at how Rama may deliver on its promise.

There are primarily three ways in which Rama makes writing a backend far more efficient:

Remove impedance mismatch between business logic and data, i.e. between your typical programming platform such as the JVM and a database such as a relational DB. One of the ways to view Rama is as a highly flexible, programmable database, which colocates data storage and processing. Colocation enables much better performance and scalability without the complexity penalty, and programmability enables you to craft the data model(s) you need, ones that fit perfectly your use cases - instead of fitting your code to the relational, document or some other limited data model.

Simplify operations by providing an all-in-one runtime with built-in fault tolerance, scalability, deployment, and monitoring. Another way to view Rama is as a cluster and application manager, or, in other words, a tool and runtime that can deploy, run, scale, and monitor your code and data. You have only a single software to set up and operate - Rama itself - instead of a bunch of application servers, Kubernetes, a couple of different databases, a monitoring tool(s), and what not.

Power up developers by providing a more powerful programming language and paradigm for distributed processing - dataflow programming. You define a dataflow program in terms of operations that perform some work upon receiving input and emit 0 to many output values to one or more other operations. You can see how this is more powerful than functions, which only "emit" a single value to a single caller. Rama is free to execute these operations when & where it is best. Thus a dataflow program is easily run in a distributed manner and is fundamentally reactive. (And you therefore don’t need to exert yourself to ensure that all relevant data is recomputed when inputs change - it is all automatic.)

A pair of motivational quotes:

Rama is a new programming platform implementing a distributed-first paradigm that will radically improve your ability to build applications. By learning Rama you’ll not only add a powerful tool to your development toolkit, you’ll learn a new way of thinking about programming.

At a high-level Rama combines what databases and stream processing systems do, except with massively enhanced capabilities. All storage is durable and replicated, and all computation is inherently fault-tolerant. Rama applications are horizontally scalable, and deployment, monitoring, and updating are seamlessly built-in.

From the Rama introduction blog post

Hopefully I have managed to persuade you that Rama is worth looking at. Let’s dive into the details, based primarily on the the introductory blog post. The post is rather long (and absolutely worth reading!), with a number of topics. These include Our Mastodon instance - on features, performance, project duration, and how these compare to Mastodon proper and to Twitter; Rama’s architecture; Mastodon on Rama - how some of the key parts of Mastodon were implemented on top of Rama.

Our implementation [of Mastodon] totals 10k lines of code, about half of which is the Rama modules and half of which is the API server.

Rama has all the data processing, indexing, and most logic in 5k lines of code. The API server is a dumb REST server in Java (and takes about as much LoC as the whole core 🤯).

On LoC: Twitter ± 1M, official Mastodon (Ruby on Rails, far worse performance than Rama’s) minimally 18k. Rama scalability: tested linear to 3* Twitter (up to some 125 servers with 2 vCPUs and 16GB ram).

[..] a Twitter-scale Mastodon implementation with extremely strong performance numbers in only 10k lines of code, which is less code than Mastodon’s current backend implementation and 100x less code than Twitter’s scalable implementation of a very similar product?

A key question that motivated the creation of Rama: “[G]iven that software is entirely abstraction and automation, why does it take so long to build something you can describe in hours?”

At its core Rama is a coherent set of abstractions for expressing backends end-to-end. All the intricacies of an application backend can be expressed in code that’s much closer to how you describe the application at a high level. Rama’s abstractions allow you to sidestep the mountains of complexity that blow up the cost of existing applications so much. So not only is Rama inherently scalable and fault-tolerant, it’s also far less work to build a backend with Rama than any other technology.

Rama’s architecture

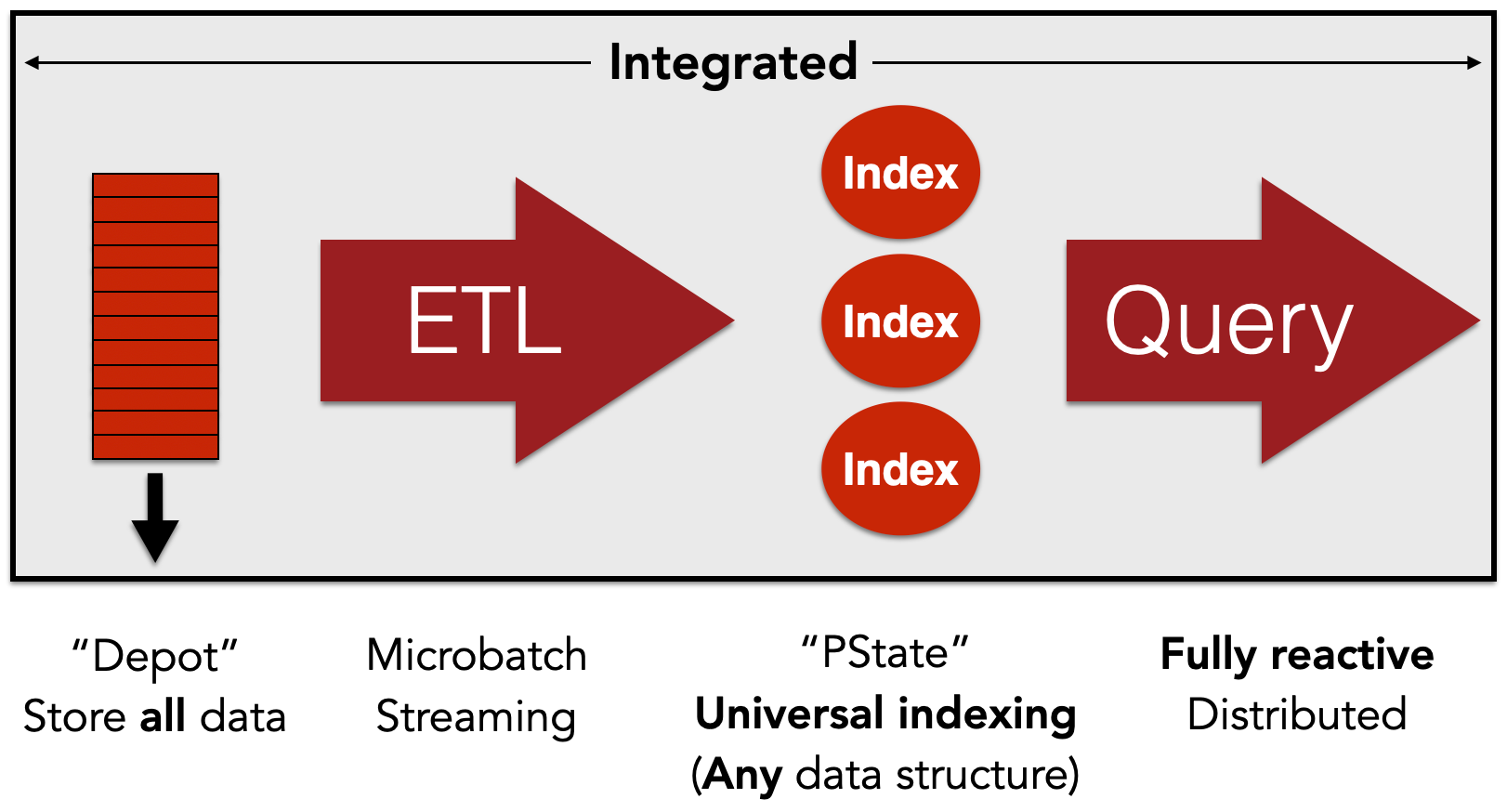

On the left are “depots”, which are distributed, durable, and replicated logs of data. All data coming into Rama comes in through depot appends. Depots are like Apache Kafka topics, except integrated with the rest of Rama.

Next are "ETL"s, extract-transform-load topologies. These process incoming data from depots as it arrives and produce indexed stores called “partitioned states”. Rama offers two types of ETL, streaming and microbatching, which have different performance characteristics. Most of the time spent programming Rama is spent making ETLs. Rama exposes a Java and Clojure dataflow API for coding topologies that is extremely expressive.

Next are “partitioned states”, which we usually call “PStates”. PStates are how data is indexed in Rama, and just like depots they’re partitioned across many nodes, durable, and replicated. PStates are one of the keys to how Rama is such a general-purpose system. Unlike existing databases, which have rigid indexing models (e.g. “key-value”, “relational”, “column-oriented”, “document”, “graph”, etc.), PStates have a flexible indexing model. In fact, they have an indexing model already familiar to every programmer: data structures. A PState is an arbitrary combination of data structures, and every PState you create can have a different combination. With the “subindexing” feature of PStates, nested data structures can efficiently contain hundreds of millions of elements. For example, a “map of maps” is equivalent to a “document database”, and a “map of subindexed sorted maps” is equivalent to a “column-oriented database”. Any combination of data structures and any amount of nesting is valid – e.g. you can have a “map of lists of subindexed maps of lists of subindexed sets”. A quote: I cannot emphasize enough how much interacting with indexes as regular data structures instead of magical “data models” liberates backend programming.

The last concept in Rama is “query”. Queries in Rama take advantage of the data structure orientation of PStates with a “path-based” API that allows you to concisely fetch and aggregate data from a single partition. In addition to this, Rama has a feature called “query topologies” [QTs], which can efficiently do real-time distributed querying and aggregation over an arbitrary collection of PStates. These are the analogue of “predefined queries” in traditional databases, except programmed via the same Java/Clojure API as used to program ETLs, and far more capable.

Rama integrates and generalizes these concepts to such an extent that you can build entire backends end-to-end without any of the impedance mismatches or complexity that characterize and overwhelm existing systems.

This colocation [of depots, ETLs, PStates, and QTs inside a single process, contrary to traditional architectures which split these to different processes or rather nodes] enables fantastic efficiency which has never been possible before.

On performance: All these concepts are implemented by Rama in a linearly scalable way. Rama also achieves fault-tolerance by replicating all data and implementing automatic failover.

Some stats: The Rama Mastodon’s module implementing timelines and profiles has: depots (13), ETLs (5: status, fanout, bloom for follow/block, core for status ops such as pin or mute, accounts), PStates (33), and query topologies (16). In 1100 LoC.

No DB vs. application logic separation here - with Rama, the product logic exists inside the system doing the indexing. Computation and storage are colocated. Rama does everything a database does, but it also does so much more.

On the process of building a backend with Rama:

When building a backend with Rama, you begin with all the use cases you need to support. For example: fetch the number of followers of a user, fetch a page of a timeline, fetch ten follow suggestions, and so on. Then you determine what PState layouts (data structures) you need to support those queries. One PState could support ten of your queries, and another PState may support just one query.

Next you determine what your source data is, and then you make depots to receive that data. Source data usually corresponds to events happening in your application

The last step is writing the ETL topologies that convert source data from your depots into your PStates.

Rama’s ETL API, though just Java [or Clojure], is like a “distributed programming language” with the computational capabilities of any Turing-complete language along with facilities to easily control on which partition computation happens at any given point.

On operations: Rama runs on a cluster of nodes, with a central “Conductor” coordinating deploys, updates, scaling, and a “Supervisor” on each node managing user code launch/teardown. Applications are deployed as “modules”, i.e. sets of depots, ETLs, PSs, QTs. They can easily consume data from other module’s depots and PSs.

From Mastodon implemented on Rama

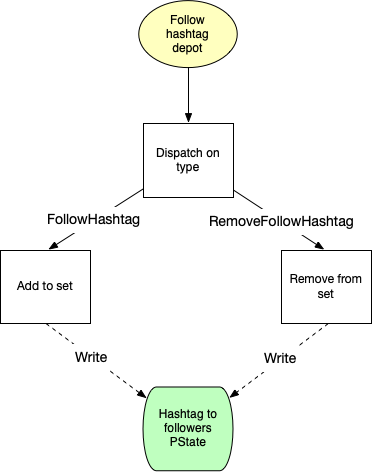

A simple feature requires little code (here about Mastodon’s tracking of who follows a hashtag):

The logic here is trivial, which is why the implementation is only 11 lines of code. You don’t need to worry about things like setting up a database, establishing database connections, handling serialization/deserialization on each database read/write, writing deploys just to handle this one task, or any of the other tasks that pile up when building backend systems. Because Rama is so integrated and so comprehensive, a trivial feature like this has a correspondingly trivial implementation.

Note: As a general rule, Rama guarantees local ordering. Data sent between two points are processed in the order in which they were sent. I.e. there is no ordering guarantees between depots.

This dataflow diagram is literally how you program with Rama, by specifying dataflow graphs in a pure Java/Clojure API. As you’ll see below, the details of specifying computations like this involve variables, functions, filters, loops, branching, and merging. It also includes fine-grained control over which partitions computation is executing at any given point.

Social graph (who follows/blocks whom) was implemented in ± 100LoC. (Twitter had to write a custom database from scratch, FlockDB, to build their scalable social graph.)

Better performance thanks to less network communication:

So whereas you always have to do a network operation to access most databases, PState operations are local, in-process operations with Rama ETLs. As you’ll see later, you utilize the network in an ETL via “partitioner” operations to get to the right partition of a module, but once you’re on a partition you can perform as many PState operations to as many colocated PStates as you need. This is not only extremely efficient but also liberating due to the total removal of impedance mismatches that characterizes interacting with databases.

[..] a big part of designing Rama applications is determining what computation goes in the ETL portion versus what goes in the query portion. Because both the ETL and query portions can be arbitrary distributed computations, and since PStates can be any structure you want, you have total flexibility when it comes to choosing what gets precomputed versus what gets computed on the fly.

Win: Colocate data that is used together - such as all information for a status and the account that posted it ⇒ instead of needing separate requests for status content, status stats, and author information, only one request is needed per status. In a traditional architecture, this would be something like 5 DB calls per a status request.

Similarly, $$accountIdToAccount and $$accountIdToStatuses entries for an account are colocated and thus queries can look at the partitions for both PStates at the same time within the same event instead of needing two roundtrips.

$$statusIdToFavoriters (to IDs of users who ❤️ it) is too partitioned by the ID of the posting account [..]. Similarly for other PStates ⇒ all information for a user and all information for that user’s statuses exist on the same partition, and performing a query to fetch all the information needed to render a status only needs to perform a single roundtrip.

This colocation makes the home timeline feature implementation very efficient, with little code:

This use case [Home timelines for individual accounts] is a great example of the power of Rama’s integrated approach, achieving incredible efficiency and incredible simplicity. Each of these PStates exists in exactly the perfect shape and partitioning for the use cases it serves.

| JH: In Rama, partitioning is clearly a key design consideration. In my daily work, I rarely think about it, and we rarely use (the very limited) partitioning in our PostgreSQL. |

PStates are partitioned, and the most common way to partition is to hash a partitioning key and modulo the hash by the number of partitions. This deterministically chooses a partition for any particular partitioning key, while evenly spreading out data across all partitions. (They are also replicated, based on the module’s replication settings, for fault tolerance / high availability.)

Interesting observations from the evolution of the design of Home Timelines w.r.t. performance:

Average fanout (the number of receivers of a status update) is ± 400 ⇒ 400x more writes to timelines than elsewhere. Initially, there was a dedicated PState (~ materialised view with full precomputed data), which worked OK. But writing it was a clear bottleneck. Also, redundant with other PSs - you can reconstruct it by looking at status of all you follow - “This can involve a few hundred PState queries across the cluster, so it isn’t cheap, but it’s also not terribly expensive.” [remember, info for each person and her status data is collocated] Ended up w/ similar approach as Twitter itself: store home timelines in-memory only [no disk], and unreplicated ⇒ increased the number of statuses we could process per second by 15x. Upon a crash, it is reconstructed from the other, persisted PSs. This tradeoff is overwhelmingly worth it because timeline writes are way, way more frequent than timeline reads and lost partitions are rare.

Timeline is effectively just a list of [author-id, status-id] pairs (capped at max 600) in a hashmap, maintained in the processes executing the ETL for timeline fanout. “This is dramatically simpler and more efficient than operating a separate in-memory database.” (Which is what Twitter did.) The in-memory home timelines and other PStates are put together to render a page of a timeline. This is paired with QT that turns [author, status] into the full info (remember, all relevant data for an author & status is colocated).

On ensuring fairness, so that posts from users with many followers do not delay other updates: propagate them iteratively, in batches of 64k, interleaving with other updates ⇒ status from a user with 20M followers will take 312 iterations of processing to complete fanout (about 3 minutes). Uses the microbatching processing approach.

Rama’s “Path” API allow you to easily reach into a PState, regardless of its structure, and retrieve precisely what you need – whether one value, multiple values, or an aggregation of values. They can also be used for updating PStates within topologies. Mastering paths is one of the keys to mastering Rama development.

Being able to represent your data using normal programming practices, as opposed to restrictive database environments where you can’t have nested definitions like this [where a value is again a struct/enum], goes a long way in avoiding impedance mismatches and keeping code clean and comprehensible.

| Apache Thrift was developed at Facebook, and “Its goal was to be the next-generation Protocol Buffers with more extensive features and more languages. Its IDL syntax is supposed to be cleaner than PB. It also offers additional data structures, such as Map and Set.” |

An interesting comment on a PState of Map[subindexed Set[Long]]:

Because the nested sets are subindexed, they can efficiently contain hundreds of millions of elements or more.

On reuse and composability via Rama macros:

a Rama macro is a utility for inserting a snippet of dataflow code into another section of dataflow code. It is a mechanism for code reuse that allows the composition of any dataflow elements: functions, filters, aggregation, partitioning, etc.

Rama’s async API is used almost exclusively in the Mastodon API implementation so as not to block any threads (which would be an inefficient use of resources).

Rama supports two ETL processing modes: streaming (faster, but with less throughput) and microbatching.

Microbatching guarantees exactly-once processing semantics even in the case of failures. That is, even if there are node or network outages and computation needs to be retried, the resulting PState updates will be as if each depot record was processed exactly once.

I didn’t mention “fine-grained reactivity”, a new capability provided by Rama that’s never existed before. It allows for true incremental reactivity from the backend up through the frontend. Among other things it will enable UI frameworks to be fully incremental instead of doing expensive diffs to find out what changed. We use reactivity in our Mastodon implementation to power much of Mastodon’s streaming API.

This fine-grained reactivity means that (1) Rama pushes only the minimal update diff to the client-side proxy listening for changes and (2) the programmer can access either the full value or only this diff, to see either the final state or only what has changed. (Clojure-specific details.)

On integration into existing architectures:

We’ve designed Rama to be able to seamlessly integrate with any other tool (e.g. databases, queues, monitoring systems, etc.). This allows Rama to be introduced gradually into any architecture.

See Integrating with other tools in the docs.

From the docs

Rama doesn’t just improve programming for applications that operate at huge scale. Its integrated approach vastly simplifies application development in general. It lets you focus on the logic of your application instead of being encumbered by one low-level hurdle after another.

The Rama model [is] a new way of organizing computing resources so that you can seamlessly scale applications while achieving world-class performance and rock-solid consistency guarantees. Rama’s programming paradigm is a dataflow-oriented approach that brings new levels of expressivity to distributed programming.

Whether you’re building the next Twitter or bootstrapping a micro-niche SaaS, Rama is a distributed-first scalable programming platform that you can use to build the entire data layer of your application.

From other sources

Rama’s Dataflow API is like a general purpose programming language for distributed programming. The heart of distributed programming with Rama are partitioners, which relocate the computation to a different partition of the module (partition ~ task) ⇒ the code before/after partitioner can run on different tasks, on different machines. Seamlessly run parallel code.

On transactions: A worker process runs task threads, which have exclusive access to particular partitions of depots and PStates. This enables transactional changes on multiple PStates, as long as relevant partitions are co-located.

On dataflow programming: An imperative program consists of functions calling functions. In a dataflow program, you think in terms of operations that wait for input. Upon receiving input, they perform some work and emit output values to one or more other operations. The mapping between operations (what) and threads (where/how) is an implementation detail. This is fundamentally reactive - operations fire in response to receiving input.

Summary

Rama’s integrated approach vastly simplifies application development in general

An integrated, scalable solution for data storage and computation together with code deployment, monitoring, and management.

Rama application design process: use cases → PState layouts → depots → ETLs. Decide what is pre-computed in ETLs vs computed on the fly in queries. Decide how to partition data to support the queries efficiently, so that data used together is stored together.

Performance: Less network hops thanks to data and processing colocation and ensuring that data used together is stored together, in the same partition.

A key skill is mastering the Specter-based Path API, for reading and updating arbitrarily structured PStates.

The design of partitioning is a key skill, ensuring good performance and scalability