What is simplicity in programming and why does it matter?

When I started with Clojure, I saw a language. Some people, when they look at it, they only see a weird syntax. It took me years to realize that in truth Clojure is a philosophy. The language embodies it, the ecosystem embraces it and grows from it, you the developer eventually soak it up.

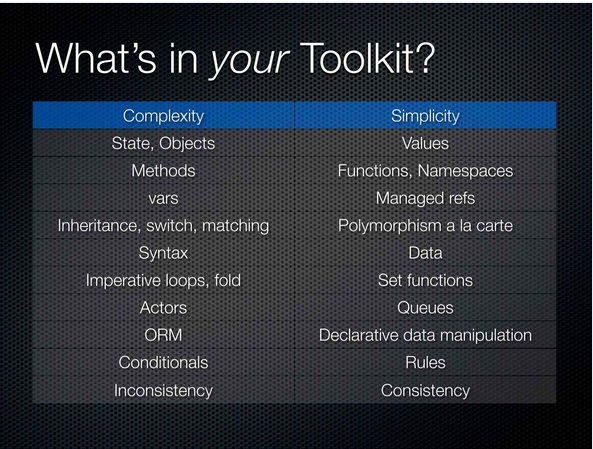

The philosophy is simplicity - on a very profound level - and, to a lesser degree, ergonomics [1]. What do I mean by simplicity and ergonomics? Simplicity is about breaking things apart into their elementary constituents that are orthogonal to each other. Ergonomics is about making it possible and convenient to combine these elements in arbitrary, powerful ways. You end up with simple things that have single responsibility and that you can combine freely to suit your unique needs. These elements are simple but also generic and thus applicable in many situations and usable in many ways. This is crucial also for flexibility:

One should not have to modify a working program. One should be able to add to it to implement new functionality or to adjust old functions for new requirements. We call this additive programming. [..] To facilitate additive programming, it is necessary that the parts we build be as simple and general as we can make them.

Examples

Let’s have a look at a few examples of simplicity in practice to get a better grasp on what it actually means.

Unix tools

The Unix tools philosophy is based on simplicity:

The tools philosophy was to have small programs to accomplish a particular task instead of trying to develop large monolithic programs to do a large number of tasks. To accomplish more complex tasks, tools would simply be connected together, using pipes.

So you have small, single-purpose elements that share a simple, well-defined, generic interface (lines of text) and thus you can combine them in many ways to achieve many different goals. You can read an access log with cat, filter only the requests from a particular IP with grep, extract just the response code with cut, sort it with sort, and get all the unique values with uniq. (The | interface is great for many purposes but actually too simple for others, which prompted the creation of the Elvish Shell, whose pipes can carry structured data.)

Clojure

Just a few examples.

Clojure gives you many of the same tools that you get in an OO language such as Java but contrary to these, you get each of them as a separate thing your are free to use and combine with others as you see fit. Java tangles polymorphism with hierarchy and code sharing (via inheritance). Java polymorphism dispatches dynamically based on the type of the target object and the inheritance hierarchy thereof. Clojure has two forms of polymorphism, the simpler protocols and the more powerful multimethods. Multimethods give you the same possibilities as Java, but separately. Again you dispatch based on a value - though here it is an arbitrary value computed from the function’s arguments, not just the type of the first argument. Typically these dispatch values are disjoint but if there is an overlap (as between :animal and 🐈) then you can define an arbitrary hierarchy of these values using Clojure’s derive. (I’ve never needed that because my needs were simple enough. Clojure allows me to use correspondingly simpler concepts and write simple code while Java forces me to always use its more complex concepts because it lacks any simpler ones.)

In Java, implementing an interface requires that you have control over the target class. That is an unnecessary and occasionally painful limitation. Clojure has protocols, which are quite similar to interfaces, but you can implement them for a class you do not control. Thus polymorphism in Clojure is independent from code ownership (to an extent). That is very powerful and useful.

A key source of simplicity in Clojure is that all data is represented by a few generic data structures and the core library provides tens of powerful functions to work with these and a few abstractions above them. In Java, everything has its own classes with their own, unique methods - effectively custom entity-specific languages. The ≈ 100 Clojure collection sequence functions I get to use again and again, with every library and framework I ever use. And similarly I reuse the few key higher-order functions to express powerful transformations. In Java, I have to learn a new "API" for each class and write tons of bespoke glue code to get data to flow from one to another. I have ranted about this before in Clojure vs Java: The benefit of Few Data Structures, Many Functions over Many Unique Classes where I had to deal with data flowing from HttpServletRequest → Apache HttpUriRequest and Apache HttpResponse → HttpServletResponse. What does this have to do with simplicity? Clojure only has a few parts, i.e. the 4 core collections, contrary to Java’s infinite number of data representations and data access forms. And it empowers you to process them with generic functions that are oblivious to the concrete domain - orthogonal to it - while in Java you are forced to write code that is much, much more case-specific.

EDN > JSON, EQL > GraphQL

Extensible Data Notation (EDN) is a Clojure parallel to JSON but it supports more data types (such as symbols, keywords, sets) and key types and, most importantly, it is extensible through "tagged literals", with some extensions included out of the box such as for dates (ex.: #inst "2021-06-13), which JSON is sorely missing, and regular expressions (#"^Hello*").

GraphQL is a graph data query language with a unique syntax. It is typically embedded in JavaScript as a string. Its Clojure parallel is EDN Query Language. The big difference is that EQL is expressed using ordinary EDN data structures - because EDN (contrary to JSON) is powerful enough. And thus, contrary to GraphQL, you do not need any special APIs to parse, transform, or programmatically generate these queries. You can simply use the old, good Clojure functions you already use million times a day. You do not need anything special to define fragments - just use data and functions. And your editor can already highlight the syntax of the queries.

We have a simple but powerful (and extensible) building block - EDN - that is able to satisfy many unexpected needs, such as EQL, while the JavaScript folks needed to invent a whole new language. (A key advantage of EDN here is that it has lists and symbols so that it can already represent mutations and parametrized queries and distinguish them from the data need definitions, as demonstrated here: [(delete-user 123)] or [({:all-employees [:name :age]} {:page-nr 3, :page-size 10})]. JSON is too limited with strings, {}, and [].)

Stu Halloway’s Reflect utility

Once upon time, Stu Halloway wanted to add a utility to Clojure to make it easier to explore Java objects, as described e.g. in Simplicity Ain’t Easy. This was his second attempt:

user=> (describe String ; (1)

(named "last")) ; (2)

=========================================

class: java.lang.String

Filters: [(named last)]

=========================================

int lastIndexOf(java.lang.String) public

int lastIndexOf(int) public

...| 1 | describe prints information about a Java class and its methods |

| 2 | We can also filter the methods shown using convenient, clearly named predicates it provides |

This solutions is not good enough - it is not simple enough. Here is the final variant:

user=>(require '[clojure.reflect :refer [reflect]]

'[clojure.pprint :refer [print-table]])

user=> (->> (reflect String) ; (1)

:members ; (2)

(filter #(.startsWith (str (:name %)) "last")) ; (3)

(clojure.pprint/print-table)) ; (4)

| :name | ... | :parameter-types | ...

|-------------+-----+---------------------------------...

| lastIndexOf | ... | [java.lang.String] | ...

| lastIndexOf | ... | [int] | ...

| ...The final solution is far less "pretty" - it requires more code, you need to learn the shape of the data, and are forced to put all the pieces together manually. But it is also far simpler - each part does a single thing and is independent from the others:

reflectleverages the ubiquitous, generic Clojure exchange interface - data; we also use a generic Clojure connection facility to connect the pieces together - the threading macro->>There is no custom API for data access - use Clojure’s general data access to get the subset of data you want

There is no custom API for filtering - use Clojure’s general data access sequence functions to filter and process the data in any way you want

Printing isn’t baked into the API anymore. Instead, there is a general purpose printing function that can print any data

What are the pros and cons?

The disadvantage is that it requires more work from you - you need to learn about the pieces (reflect, print-table) and understand the data they work with. Filtering is more verbose. On the other hand, you can add convenience wrappers of your own, ones that fit your needs 100%, should you desire so - because now you can.

The advantage is that you get a generic printing function that you can use for any, completely unrelated, needs and that you get the information about the class as data. Data that you can process leveraging the multitude of functions and libraries you already know and to purposes other than printing, purposes the author did not expect. And you do not need to learn any new "entity specific language" of method filtering predicates.

Discussions of simplicity

I listened to three great talks on the topic of simplicity - Rich Hickey’s Simple Made Easy and Stuart Halloway’s talks Radical Simplicity and Simplicity Ain’t Easy. I can heartily recommend all of them to any student of the topic. A few highlights and reflections follow.

Simple Made Easy

Simplicity is hard work. But, there’s a huge payoff. The person who has a genuinely simpler system — a system made out of genuinely simple parts, is going to be able to affect the greatest change with the least work. He’s going to kick your ass. He’s gonna spend more time simplifying things upfront and in the long haul he’s gonna wipe the plate with you because he’ll have that ability to change things when you’re struggling to push elephants [JH: of their complex codebase] around.

Why? Because our ability to affect changes is limited by our understanding of the system - where to change it, the impact of the change. And the more complex it is, the less we can understand it.

What benefits do we get from simplicity? We get ease of understanding, right? That’s sort of definitional. I contend we get ease of change and easier debugging. Other benefits that come out of it that are sort of on a secondary level are increased flexibility. [..] As we make things simpler, we get more independence of decisions because they’re not interleaved, so I can make a local decision.

[..] we can create precisely the same programs we’re creating right now with these tools of complexity with dramatically, drastically simpler tools.

You want to start seeing interconnections between things that could be independent. That’s where you’re going to get the most power.

Programming, when stripped of all its circumstantial irrelevancies, boils down to no more and not less than very effective thinking so as to avoid unmastered complexity, to very vigorous separation of your many different concerns.

My reflections on Radical Simplicity

A common consequence of complexity is that you have to touch too many places to get a change in.

We get trapped at local maxima in the solution space (w.r.t. simplicity) because we do not spend enough time on a careful analysis and deep thought and spend too much incrementally improving.

What do we know about simplicity?

We have seen a couple of examples of simplicity in practice. What have I learned from those and the aforementioned talks?

Simple means not tangled; there aren’t multiple things, concerns, roles, concepts or dimensions interleaved together. It thus also depends on the number and nature of interactions and their shape or tangleness. When we combine things together, we want to make composites (where the elements can be separated again) rather than compounds (where they are inextricably mixed and interleaved). Simplicity is objective because - if we can distinguish them - we can count how many simpler elements are there, tangled together.

Simple is not "pretty" because you are exposed to the (simple) constituent parts and the plumbing to combine them together, it is more verbose. (Though you can easily provide a custom convenience wrappers.)

What is simple is not necessarily easy. "Easy" means "close to me" and thus "accessible to me". A thing is easy for me to understand when it is close to what I already know, when I am somewhat familiar with it. Nothing wrong with that but simplicity is far more important - and often it requires some measure of novelty, which makes it by definition not easy.

Simplicity enables change and thus cheaper maintenance and allows for a more robust software.

We want to look for simple elements - "simples" - that are also powerful, often thanks to being generic, i.e. not overly limited to what they apply to. For example data is generic - it can carry any information.

Simplicity is not easy to achieve. It requires a fair amount of deep thinking, hard work, and likely multiple attempts to uncover.

Summary

Clojure - the language and its ecosystem - is about simplicity. Simplicity means "untangling things" (such as concepts) and requires hard work. The result might not be pretty or easy to consume for a particular person but it provides greater flexibility and robustness and hugely pays off in the long run.

update takes fn & args, how that plays with → etc.